Kenji Yamamoto

Kenji Yamamoto is Professor Emeritus of Kyoto University and Professor Emeritus of Ishikawa Prefectural University.

He received his Ph.D. from the Faculty of Agriculture, Kyoto University, in 1979. He started his professional career in 1976 as a Research Associate in the Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Agriculture, Kyoto University. He was promoted to Professor in the Division of Integrated Life Science, Graduate School of Biostudies, Kyoto University in 1999. After retiring in 2010, he became a Professor in the Research Institute for Bioresources and Biotechnology at Ishikawa Prefectural University. After retiring from the research institute in 2017, he became a specially appointed professor for 2 years and in 2019 moved to the Center for Innovative and Joint Research, Wakayama University, where he served as Visiting Professor until his final retirement in 2025.

CHIBA Yasunori

Director General, Department of Life Science and Biotechnology (LS-BT), National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST).

He obtained a Ph.D. in Agricultural Science from Tohoku University in 1994. He then served as a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Research Fellow, Postdoctoral Fellow at Kirin Brewery Co., Ltd., and Industrial Technology Researcher at the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO). Since 2001, he has been with AIST, where he advanced from tenure-track Researcher to Senior Researcher (2006), Research Team Leader (2014), Director of the Cellular and Molecular Biotechnology Research Institute (2022), Deputy Director-General of LS-BT (2023), and his current position (2025).

Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (ENGase) is an enzyme widely distributed among various organisms and known to hydrolyze N-glycans. Recent studies have demonstrated that strategic modification of its catalytic residues enables its conversion into a glycosynthase, thereby facilitating the chemoenzymatic remodeling of N-glycan structures.

In this series, we will discuss recent progress in glycoengineering-related ENGase research by leading experts in each field.

Progress in the field of glycoscience requires the synthesis and construction of oligosaccharides to elucidate the significance and function of carbohydrates. The creation of new oligosaccharides and the addition of oligosaccharides to a compound to give it a useful function are important research subjects in glycotechnology. Chemical methods for the synthesis of oligosaccharides are well established. However, these are labor-intensive and involve complicated steps of protection and deprotection. Conversely, enzymatic methods of oligosaccharide synthesis have advantages because of their high stereo- and regio-selectivity. Thus, the construction of oligosaccharides can be carried out by using glycosyltransferases in a process that is similar to the biosynthetic process in living organisms. In 1982, Wong et al. reported an elegant method for the regeneration of sugar nucleotides coupled using glycosyltransferases1. Since then, various methods using enzymes have been recognized as effective chemo-enzymatic strategies for carbohydrate synthesis. The chemo-enzymatic method combines the flexibility of chemical synthesis with the specificity of enzymatic synthesis. The use of this method was extended, not only to the synthesis of homogeneous glycoconjugates and novel oligosaccharide clusters, but also to unusually glycosylated natural products.

In recent years, great progress has been made toward producing structurally well-defined and homogeneous oligosaccharides and glycoconjugates. The need for functional studies and biomedical applications has stimulated the development of new chemical and biochemical methods for preparing structurally homogeneous oligosaccharides and glycoconjugates.

In contrast to chemical methods, enzymatic glycosylation usually provides effective control of the anomeric configuration and high regio-selectivity without the need for protecting groups. Commonly used for enzymatic glycosylation, glycosyltransferases have been explored for the synthesis of glycosylated compounds. These natural enzymes for producing glycosidic bonds using sugar nucleotides as the donor substrate usually have stringent substrate specificity. Conversely, glycosidases have a hydrolytic function and break glycosidic linkages during carbohydrate metabolism. Despite the inherent nature of glycosidases, many glycosidases have transglycosylation activity that involves the transfer of a carbohydrate moiety to the hydroxyl groups of various compounds, and interest in their transglycosylation activity for glycosylating compounds is increasing. In contrast to glycosyltransferase-catalyzed reactions, glycosidase-catalyzed transglycosylation has several advantages, including the use of readily available donor substrates and the relative ease of access to the enzymes. Most glycosidases can be easily obtained in large amounts from various sources. Furthermore, in contrast to glycosyltransferases that extend oligosaccharides by adding a monosaccharide one at a time, endoglycosidase can transfer a large oligosaccharide en bloc to an acceptor in a single step, in a concise manner through its transglycosylation activity.

Protein glycosylation is essential to many vital biological processes, such as cell–cell signaling, development, and immune response. It represents the most diverse form of post-translational modification, playing a key role in protein folding, and crucially affecting many important protein properties, such as conformation and stability, and circulatory lifetime. Among the numerous approaches developed to obtain glycopeptides and glycoproteins in homogeneous form2, the endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (ENGase) approach is one of the most useful synthetic tools applied in the field of glycoengineering. This review examines ENGase enzymes from various perspectives and highlights their use in glycoengineering.

ENGase is the endoglycosidase known to hydrolytically cleave the N, N’-diacetylchitobiose moiety (GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc) in the core region of asparagine-linked (N-linked) oligosaccharides of various glycopeptides and glycoproteins2. All of these N-linked oligosaccharides contain the same core pentasaccharide unit (Man3GlcNAc2) linked to asparagine residues of peptides or proteins. ENGase possesses a unique enzymatic action in that one N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residue remains bound to the peptide or the protein. Because the enzyme can separate intact oligosaccharide and aglycon (the non-sugar part of a glycoside molecule) without causing damage, this endoglycosidase is a highly convenient and indispensable tool used in the field of glycobiology for characterization of released oligosaccharides and remaining peptides or proteins3.

ENGase is widely distributed among various organisms such as bacteria, yeast, fungal, plant, mice, and humans, and various distinct enzymes with different glycan specificity have been identified. Recently ENGases were identified in intestinal bacteria. Variations in N-glycan structures within the intestinal tract are considered to influence the composition of gut microbiota, suggesting that microbial communities occupying the gut may be enriched through ENGase activities. Furthermore, substrate acquisition by microbes appears to depend on the specificities of their ENGases towards different types and structures of N-glycans4. Microbes display a wide range of glycan specificities including high-mannose, hybrid, and/or complex type N-linked glycans. It was recently reported that human gut microbes employ evolutionary strategies to express functionally distinct ENGases, encoded within separate PULs (polysaccharide utilization loci) in different gut bacteria, to optimally metabolize the same N-glycan substrate in the gastrointestinal tract5.

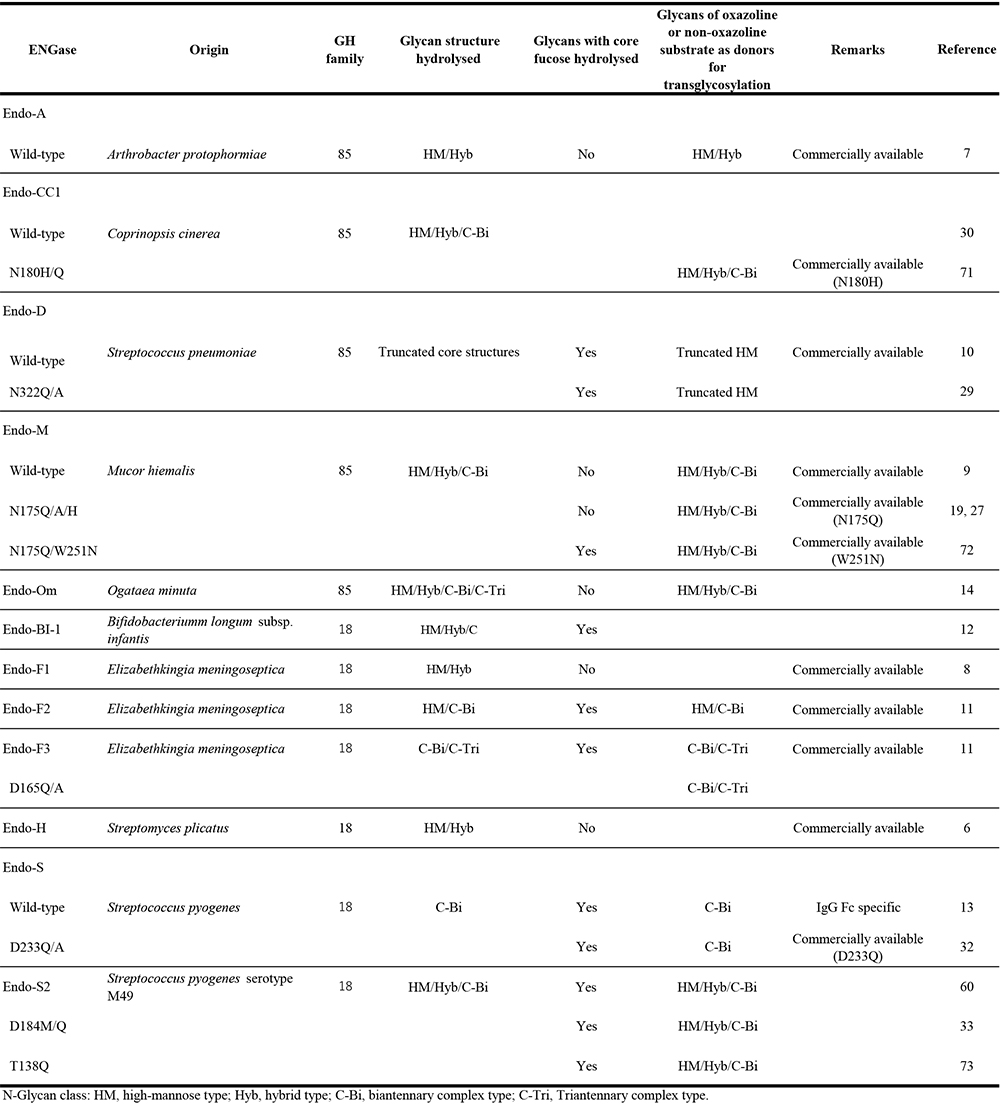

The substrate specificity of ENGase is an important consideration for determining its usefulness as a glycoengineering tool. In glycoengineering applications, native microbial enzymes are more readily available than those derived from animal, plant, or other sources, even though recombinant enzymes can be produced through gene database-reliant genetic engineering. However, some identified microbial ENGases act on high-mannose or hybrid type N-glycans, or on both, but often do not act on the complex type N-glycans that are present in most animal-derived glycoproteins. They include ENGases from Streptomyces plicatus (Endo-H)6, Arthrobacter protophormiae (Endo-A)7, and Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (Endo-F1)8. On the other hand, ENGases from Mucor hiemalis (Endo-M)9, Streptococcus pneumoniae (Endo-D)10, Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (Endo-F3)11, Bifidobacterium longum sp. infantis (Endo-Bl-1)12, Streptococcus pyogenes (Endo-S and Endo-S2)13 and Ogataea minuta (Endo-Om)14 are reported to act on the complex type N-glycans of glycopeptides or/and glycoproteins. Most of these ENGases described above are commercially available and used as efficient tools in glycoengineering studies (Table 1).

Based on primary structures, there are two types of ENGase in the Carbohydrate Active enZymes (CAZy) Database: one is glycoside hydrolase (GH) family 18 ENGase and the other, GH family 85 ENGase. All GH18 family enzymes contain two carboxylic acid residues in the active site, specifically glutamic acid and aspartic acid. In contrast, the GH85 family enzymes contain only a single glutamic acid residue in the active site, while the other essential catalytic residue is asparagine. All ENGases have similar (β/α)8-TIM barrel structures consisting of eight α-helices and eight parallel β-sheets. Despite exhibiting the same enzymatic activity, most ENGases within a GH family share only 25-35% sequence identity, suggesting that there are many differences between these enzymes that show distinct catalytic mechanisms and divergent substrate specificities.

Many glycosidases exhibit transglycosylation activities that involve the transfer of a carbohydrate moiety to the hydroxyl groups of various compounds, in addition to hydrolytic activities that involve the hydrolysis of glycosidic linkages15. The transglycosylation activity of endo-type glycosidases is especially useful for transferring and adding an oligosaccharide to compounds bearing hydroxyl groups16. Therefore, exploiting transglycosylation activity of endoglycosidase is an extremely useful means of glycosylating peptides and proteins. The transglycosylation activity of ENGase is thought to catalyze the following reaction:

R-GlcNAc-GlcNAc-Asn (glycoside donor) + GlcNAc-Asn-R’ (acceptor) →

R-GlcNAc-GlcNAc-Asn-R’ (transglycosylation product) + GlcNAc-Asn

(R: oligosaccharide, R’: peptide or protein)

However, not all ENGases possess transglycosylation activity. To the best of our knowledge, Endo-H, a popular tool for liberating oligosaccharides, does not possess transglycosylation activity and cannot be used for glycosylation. Meanwhile, bacterial enzymes, such as Endo-A, and fungal enzymes, such as Endo-M, are extensively used as glycosylation tools for synthesizing glycopeptide and glycoprotein with N-linked glycan17. Endo-A is commonly employed to transfer high-mannose type glycans from glycopeptides derived from hen’s egg white to various compounds. In contrast, Endo-M is used for transferring complex type glycans from glycopeptides extracted from hen’s egg yolk18. Initially, it was thought that only ENGases belonging to GH85 have transglycosylation activity, but later it was found that some ENGases belonging to GH18 also have transglycosylation activity.

It is becoming widely accepted that the enzymatic method using ENGase is the most efficient and practical glycosylation approach used in glycoengineering. ENGase enables the addition of a glycan moiety to a GlcNAc-containing compound (peptide or protein) in a single step, in a regio- and stereo-selective manner, without requiring any protecting groups. However, transglycosylation activity of ENGase is relatively low compared to its hydrolytic activity, and the resulting product does not accumulate significantly. A major problem is the enzymatic re-hydrolysis of the transglycosylation product as a substrate for ENGase. To address this issue, glycosidase mutants with abolished hydrolysis activity but possessing transglycosylation activity have been engineered, and then subjected to site-directed mutagenesis of catalytic residues in Endo-M belonging to GH85. One of these mutants, Y217F, revealed a much higher affinity for the acceptor substrate than the wild type, suggesting that removal of the hydroxyl group on the tyrosine residue may promote the substrate binding at the catalytic site19. Although a few similar mutant enzymes were obtained they were still capable of hydrolyzing the product and therefore not suitable as a tool for glycoengineering.

Using site-directed mutagenesis to generate mutant enzymes known as “glycosynthases,” Withers and Planas conducted studies aimed at improving GH-catalyzed transglycosylation reactions20.21. Specifically, in these studies, the catalytic nucleophile of the retained glycosidases was replaced with a non-participating residue, allowing these mutants to process activated donors (such as glycosyl fluorides) with the opposite anomeric configuration to the natural substrate, while preventing hydrolysis of the reaction product. These features of glycosynthases contribute to enhancing ENGase-catalyzed transglycosylation.

It is known that transglycosylation proceeds via a double displacement mechanism mediated by two active residues: a catalytic nucleophile and a general acid/base22 of GH enzyme. In general, glycosidases hydrolyze glycosidic bonds through either an inverting or retaining mechanism23. Both mechanisms involve oxocarbenium-ion-like transition states and a pair of carboxylic acids, typically aspartate and glutamate residues. However, exceptions exist, such as certain N-acetylhexosaminidases that lack a catalytic nucleophilic residue and act via a substrate-assisted mechanism24. In substrate-assisted catalysis, a functional group within a substrate contributes to catalysis by an enzyme. In this case, the catalytic nucleophile is the 2-acetamido group on the GlcNAc residue of the substrate undergoing hydrolysis. Some microbial ENGases act via a substrate-assisted mechanism that involves participation of the 2-acetamido group through formation of a 1,2-oxazolinium ion intermediate25. These ENGases belonging to GH family 85 are assumed to catalyze their hydrolysis and transglycosylation reactions via an oxazolinium ion intermediate. Other bacterial ENGases belong to GH family 18, and their catalytic mechanism is analogous to those of some GH family 18 chitinases and some GH family 20 N-acetylhexosaminidases11. These results inspired the use of sugar oxazolines as donor substrates in transglycosylation reactions of ENGases, as oxazoline compounds mimic the transition state. Shoda et al. demonstrated that disaccharide oxazoline can serve as an activated glycosyl donor substrate for certain GH family 85 ENGases. Furthermore, they demonstrated a simple method to readily synthesize complex oligosaccharide oxazolines without the need for any protecting groups25. The synthetic oligosaccharide oxazolines were proved to be excellent substrates for the transglycosylation activity of ENGases. This observation prompted investigation of the feasibility of synthetic oligosaccharide oxazolines as suitable substrates for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of glycopeptides and glycoproteins. Later, these synthetic sugar oxazolines were also shown to be effective donor substrates for transglycosylation reactions catalyzed by ENGases belonging to GH family 18. In fact, the combination of ENGase with synthetic sugar oxazolines typically resulted in the formation of the desired glycopeptides in yields of 75–85%.

Although the use of synthetic sugar oxazolines is effective for syntheses of transglycosylation products, the yield has remained unsatisfactory, due to rapid hydrolysis of the product by wild-type ENGase. One solution to this problem is to develop unique ENGase-based glycosynthases that lack hydrolytic activity toward the product but retain the ability to use the sugar oxazolines as donor substrates26. For this purpose, site-directed mutagenesis of ENGase has been performed to generate glycosynthase mutants. Umekawa et al. reported the discovery of the first glycosynthase derived from ENGase, obtained using a Man9GlcNAc N-glycan oxazoline as the activated donor substrate. For this Endo-M mutant enzyme, variation was introduced at the asparagine-175 residue, which promotes formation of the sugar oxazolinium ion intermediate. Mutation at this critical residue from asparagine to glutamine (N175Q) abolished hydrolytic activity while retaining the ability to use activated glycan oxazolines as substrates for transglycosylation27.

These results, involving mutation of a key residue that promotes formation of the oxazolinium ion intermediate during catalysis, have been extended to GH family 85 ENGases, including Endo-A28, Endo-D29, Endo-CC30 (from the basidiomycete Coprinopsis cinerea) and others. The resulting glycosynthases have proven useful for chemo-enzymatic syntheses of glycopeptides and glycoproteins. Furthermore, Endo-S was shown to possess transglycosylation activity31, and glycosynthase mutants (D233A and D233Q) were successfully prepared from Endo-S32. These Endo-S mutants are highly specific for Fc antibody glycan and represent the first example of glycosynthases derived from the GH family 18 ENGases. They can transfer complex type N-glycans from the corresponding glycan oxazoline to deglycosylated Rituximab, forming a new and homogeneous glycoform of the antibody without hydrolysis of the product. In addition, they are capable of performing Fc glycan remodeling on intact full-size antibodies. Additionally, Li et al. generated a glycosynthase by introducing the D184M mutation into Endo-S2, a GH family 18 ENGase from a serotype of Streptococcus pyogenes. The resulting glycosynthase exhibited much higher efficiency and more relaxed substrate specificity for Fc antibody glycan33. Since this glycosynthase mutant enzyme is specific for IgG glycans, it is widely used for removal and remodeling of IgG sugar chains and serves as a valuable tool for glycoengineering of antibodies.

There are several other reports regarding useful glycosynthase mutants of ENGases. In the future, the discovery of novel and efficient glycosynthases and use of glycan oxazolines as donor substrates may be critical for developing large-scale enzymatic syntheses of glycoproteins and glycopeptides.

Although peptides can be easily synthesized chemically, N-linked glycopeptides are relatively difficult to synthesize, not only because the chemical synthesis of N-glycans involves complicated steps, but also due to the challenge of coupling them with peptides. The use of a chemoenzymatic synthesis method is the most effective approach to address these issues. The most common chemoenzymatic synthesis of glycopeptides involves the chemical synthesis of an N-acetylglucosaminyl peptide, followed by enzymatic transfer of the N-glycan using ENGase. For peptide synthesis, the N-acetylglucosaminyl peptide is firstly prepared using the Fmoc strategy, employing Fmoc-Asn-GlcNAc as the building block instead of Fmoc-Asn. Finally, the glycopeptide is obtained by ENGase-catalyzed transglycosylation using the N-acetylglucosaminyl peptide and the natural N-glycan as the glycosyl donor. Using this typical chemoenzymatic method, several biologically interesting glycopeptides have been synthesized using Endo-M. These include glycosylated peptide T34, glycosylated calcitonin35, and glycosylated glucagon36. This method can also be used to glycosylate glutamine residues in peptides. Although the biological addition of oligosaccharides to glutamine residues is impossible, glycopeptides with a glutamine-linked oligosaccharide can be synthesized by this chemoenzymatic method, using Fmoc-Gln-GlcNAc as the building block instead of Fmoc-Gln for peptide synthesis. Glycosylated substance P37 and glycosylated yeast α-mating factor38 were synthesized by this method. These glycosylated peptides were found to be more stable against protease digestion and thermal treatment than their native peptides. This chemoenzymatic method using Endo-M was also applied to the synthesis of multivalent glycopolymers39 and glycosylated insulin40 Moreover, C34 glycopeptide, a fragment of the C-terminal domain of an HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein that exhibits potent anti-HIV activity, was also synthesized using the transglycosylation activity of Endo A41 Also, homogeneous CD52 antigen was prepared using this chemoenzymatic synthesis42.

With various methods for synthesizing GlcNAc-containing peptides, many glycopeptides have been prepared by using the glycosynthase mutant of ENGase and N-glycan oxazolines as donors. These include glycosylated peptides derived from partial fragments of HIV envelope glycoproteins, glycosylated variants of pramlintide (which is a peptide-based anti-diabetic drug), and others43.

In the context of glycoproteins synthesis using natural proteins and ENGase-catalyzed glycosylation, Hojo et al. achieved chemo-enzymatic synthesis of saposin C, a hydrophobic glycoprotein, by employing the transglycosylation activity of Endo-M-N175Q to attach a synthetic glycan to the synthetic protein, using the corresponding glycan oxazoline as the donor substrate44. This study demonstrates the feasibility of a chemoenzymatic approach for constructing glycoproteins for structural and functional studies.

Naturally occurring glycoproteins exhibit a high degree of heterogeneity in their oligosaccharide moieties. The diverse glycosylation patterns of glycoproteins may pose challenges for biological and pharmaceutical applications and hinder understanding of their function. Most of the recombinant therapeutic glycoproteins are currently produced by overexpression in Chinese Hamster ovary (CHO) cells. However, these recombinant glycoproteins are produced as identical proteins that differ only in their glycan structures. Thus, a method capable of producing homogeneous glycoproteins is required. Regarding such methods, attempts have been made to exploit both the hydrolytic and transglycosylation activities of ENGases for N-glycan remodeling in glycoproteins. For example, bovine RNase B contains a single high-mannose type glycan consisting of five to nine mannose residues. Umekawa et al. introduced a sialylated complex type glycan into GlcNAc-containing RNase B, after Endo-H treatment to remove the heterogeneous N-glycans, via Endo-M-N175Q glycosynthase-catalyzed transglycosylation using a synthetic sialylated complex type oligosaccharide oxazoline45. The resulting product was a homogeneous sialoglycoprotein. This represents the typical remodeling of natural glycoproteins, converting a high-mannose type glycan into a sialylated complex type, and demonstrates the feasibility of remodeling or exchanging glycans on glycoproteins and glycopeptides. Using this concept and the activities of ENGase, the large high-mannose type glycans in recombinant glycoproteins or glycopeptides produced by recombinant yeast systems can be exchanged or remodeled into sialo-complex type oligosaccharides, which are compatible with human systems and are not synthesized by microorganisms. This remodeling strategy could also be applied to the production of various biopharmaceuticals, many of which are currently manufactured using recombinant yeast systems.

Recently, enzyme replacement therapy has attracted a great deal of attention. Glycan remodeling is an important strategy for the preparation of enzymes for replacement therapies. It is well known that protein transport to lysosomes, which are rich in hydrolytic enzymes, is mediated by mannose-6-phosphate receptors on the cell surface. These receptors recognize high-mannose type glycans containing mannose-6-phosphate (Man-6-P) residues46. The production of glycoproteins containing phosphorylated mannose residues in N-glycan is therefore important for improving the enzyme replacement therapies for the treatment of lysosomal storage disorders. The development of enzyme replacement therapy using yeast with phosphorylated N-glycans has long been pursued47,48, but as a new approach, the use of ENGase-mediated transglycosylation to produce enzymes bearing phosphorylated glycans has been investigated. Priyanka et al. reported the first phosphorylated glycoprotein to be produced using ENGase-mediated transglycosylation. A synthetic tetrasaccharide bearing Man-6-P residues was converted into an oxazoline and transferred to de-glycosylated RNase B by Endo-A, yielding the corresponding phosphorylated glycoprotein49. Yamaguchi et al. also reported the synthesis of phosphorylated glycoproteins containing Man-6-P by ENGase-catalyzed glycan remodeling of the deglycosylated RNase B50. Zhang et al. chemically synthesized truncated Man-6-P-glycan oxazolines and used them for ENGase-catalyzed glycan remodeling of recombinant human acid α-glucosidase (rhGAA), an enzyme used for treatment of Pompe disease, a disorder caused by a deficiency of the glycogen-degrading lysosomal enzyme51. Endo-F3 remodeled rhGAAs retained full enzyme activity and exhibited 20-fold increase in receptor binding affinity. Recently, Shinoda et al. demonstrated that by using recombinant silkworms to produce α-L-iduronidase and replacing its glycans with chemically synthesized phosphorylated glycans, they were able to ameliorate clinical signs in macaques with mucopolysaccharidosis I52. This remodeling approach is expected to become an increasingly valuable tool in glycoengineering.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are effective therapeutic glycoproteins used for the treatment of cancers, inflammatory disorders, and infectious diseases53. Most therapeutic mAbs belong to the IgG class and contain an N-glycan. A typical IgG class antibody consists of two heavy chains and two light chains that form three distinct domains: two identical Fab domains and one Fc domain54. The Fc domain, a homodimer of the heavy chain, carries a conserved N-glycan at Asn-297, which is typically a biantennary complex type glycan55. This domain is involved in the recruitment of immune cells by binding to Fc receptors (FcγRs) on their cell surface and directly initiates immune responses, including phagocytosis, immune cell activation, and cytokine stimulation toward antigen-displaying targets. The glycosylation of the Fc domain mediates interactions with FcγRs and regulates antibody-dependent effector functions, including antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), which involves activation of natural killer cells to induce cancer cell lysis, and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), which triggers target cell lysis through the complement pathway. Therefore, glycosylation has profound effects on biological function and overall therapeutic efficacy. For example, core-fucosylation of the N-glycan in the Fc domain reduces IgG antibody binding to the Fc receptor, and the lack of core-fucose in the N-glycan would dramatically enhance ADCC56. The galactose residue at the non-reducing end of the Fc N-glycan also improves ADCC and CDC of IgG antibodies57. Moreover, terminal sialic acid moieties of Fc N-glycan have also been reported to be crucial for the anti-inflammatory activity of intravenous IgG58.

As the N-glycan structures attached to the IgG Fc domain are generally heterogeneous, IgGs engineered to be homogeneously glycosylated with functional N-glycans may improve the efficacy of antibodies. Because mammalian cell lines, such as CHO, are commonly used as hosts, natural and recombinant antibodies are usually produced as glycoproteins with heterogeneous glycoforms. Considering these facts, glycoengineering of Fc N-glycan may become a valuable approach to improve the function of IgG antibodies. It is therefore necessary to develop IgG antibodies with well-defined N-glycans, and the chemoenzymatic remodeling of N-glycan using ENGase has attracted a great deal of attention. Against this background, Wei et al. reported deglycosylation and reglycosylation of the Fc domain expressed in the yeast Pichia pastoris using ENGase59. This demonstrated that glycan remodeling on a recombinant Fc domain of a human IgG is feasible. The process is briefly outlined as follows: the recombinant Fc domain with heterogeneous N-glycans was produced in yeast, and oligomannosidic glycans were removed by Endo-H to yield a GlcNAc-Fc domain. Then, various high-mannose type N-glycans as donor substrates were transferred to the GlcNAc moiety of the Fc domain by Endo-A, generating Fc domains with homogeneous glycoforms. Moreover, Goodfellow et al. reported that Endo-S exhibits high hydrolytic and transglycosylation activity towards complex type N-glycans on IgG Fc domains, with or without fucosylation31. Endo-S and Endo-S2, produced by Streptococcus pyogenes and its serotype M49, respectively, show remarkable specificity for the N-glycan at Asn-297 of IgG, making them ideal tools for IgG glycoengineering. Notably, Endo-S2 demonstrates a much broader substrate specificity than Endo-S, which is specific for biantennary complex type N-glycans on the Fc domain60. Endo-S2 can essentially deglycosylate all major types of Fc N-glycans. Glycoengineering of IgG using these enzymes has been frequently performed.

Huang et al. demonstrated that glycosynthase mutants of Endo-S can transfer complex type N-glycans from the corresponding glycan oxazoline to deglycosylated Rituximab, forming a new homogeneous glycoform of the antibody without hydrolysis of the product32. These mutants can also perform Fc glycan remodeling on intact full-size antibodies. This method features two steps: (1) trimming of the natural glycoforms of IgG with Endo-S to generate the deglycosylated IgG with the innermost Fuc α1,6GlcNAc disaccharide or the defucosylated GlcNAc monosaccharide; (2) transglycosylation catalyzed by Endo-S mutants (D233A and D233Q), leading to transfer of a chemically synthesized N-glycan oxazoline onto Fucα1,6GlcNAc-IgG or GlcNAc-IgG, thereby generating a glycoengineered antibody with a well-defined N-glycan structure. Several studies have adopted the above chemoenzymatic method for efficient glycosylation remodeling of IgG N-glycans with Endo-S mutants. Lin et al. used Endo-S and its mutants for Fc glycan remodeling to generate a series of glycoforms of antibodies61, and found that a biantennary N-glycan structure with two terminal α-2,6-linked sialic acids was a common optimized structure for enhancing ADCC, CDC, and anti-inflammatory activities. The usefulness of Endo-S2 glycosynthase mutants was exemplified by efficient remodeling of the N-glycan on two mAbs, Rituximab and Herceptin62. These results stimulated further studies on the remodeling of entire biotherapeutic mAbs. Rituximab was frequently used to demonstrate Fc N-glycan remodeling. This mAb targets CD20, and most N-glycans attached to its Fc domains are known to be core-fucosylated. The remodeling of Rituximab with the Endo-S2 mutants demonstrated the detrimental effect of core-fucosylation on effector functions63. Herceptin is a therapeutic mAb widely used for the treatment of breast cancer and binds to the HER2 receptor on breast cancer cells, inducing ADCC to lyse tumor cells. For N-glycan remodeling of Herceptin, the antibody was first deglycosylated with Endo-S2 and α-1,6-fucosidase from Lactobacillus casei to generate GlcNAc-Herceptin and then remodeled into a sialylated biantennary complex type N-glycan lacking core fucose using Endo-S2-D184M glycosynthase with the corresponding glycan oxazoline as the donor substrate64. This Herceptin variant with an afucosylated glycoform has been demonstrated to exhibit enhanced ADCC. Kurogochi et al. used the Endo-S-D233Q mutant along with other glycosynthase mutants derived from various ENGases to construct a relatively large glycoform library of Herceptin derivatives produced in transgenic silkworm cocoons, including both full-size and truncated Fc with N-glycans65. Using the glycoform library of Herceptin, Fc-receptor binding was assessed and cell-based assays were performed. The results revealed that glycoform composition influences ADCC, and demonstrated that, in the presence of core fucose, sialylation significantly decreases ADCC, whereas sialylation has no impact on ADCC in the absence of core fucosylation. These discoveries expanded the scope of glycoengineering for N-glycan remodeling of antibodies. Giddens et al. reported the site-selective remodeling of the N-glycans of both the Fc domain (attached to Asn-297 of the heavy chain) and the Fab domain (attached to Asn-88 of the heavy chain) of Cetuximab, a therapeutic mAb used for treatment of a variety of cancers66. This work was accomplished using the high selectivity of the Endo-F3-D165A glycosynthase mutant, which glycosylates only core-fucosylated GlcNAc residues, and the Endo-S-D233A glycosynthase mutant, which specifically glycosylates GlcNAc residues at Asn-297 of IgGs. The glycoengineered Cetuximab demonstrated increased Fc receptor affinity and significantly enhanced ADCC activity.

Some processes have been investigated to enable large-scale production of remodeling antibodies. Iwamoto et al. attempted an effective one-pot transglycosylation by combining Endo-S-D233Q and Endo-M-N175Q mutants with an intact sialoglycopeptide as the donor substrate, without using glycan oxazoline67. Tang et al. reported a one-pot strategy for N-glycan remodeling of IgG, using Endo-M to cleave glycopeptide and Endo-S-D233Q to transfer sialoglycopeptide as donor substrates68. The preparation of immobilized Endo-S2 and its glycosynthase mutant D184M using recombinant microbial transglutaminase has also been reported for chemoenzymatic glycan remodeling of antibodies69. Furthermore, Liu et al. reported an interesting study on the glycoengineering of Herceptin expressed in yeast cells, following remodeling of the recombinant antibody. They produced the recombinant antibody carrying polymannosylated glycans using a gene-edited Pichia pastoris and remodeled its glycans by deglycosylation with Endo-H or Endo-E (from Enterococcus faecalis), followed by glycosylation with Endo-S2-D184M using the corresponding glycan oxazoline as the donor substrate. This method appears suitable for large-scale production of antibody with desirable glycoforms70.

The use of enzymes in the construction of glycans is highly advantageous in glycoengineering because enzymatic reactions proceed under mild conditions (e.g., ambient temperature and neutral pH) and exhibit very high substrate specificity with excellent regioselectivity. In addition, various techniques, such as genetic and protein engineering, can be employed to modify enzyme specificity and to design enzymes that are active against a broader range of substrates. Glycan remodeling technology using ENGase is expected to enable large-scale production of recombinant biopharmaceuticals such as monoclonal antibodies. In the future, an efficient and automated glycan synthesis process based on chemoenzymatic methods will likely be developed to facilitate precise glycan preparation. Effective application of these chemoenzymatic approaches will lead to new developments in glycoscience.